Home Page

Home Page

Home Page

Home Page

THE LOCKED JOURNAL

Page 4.

Before I go on to describe the incidents of the voyage, I must narrate a laughable story, in which I played a very

wicked part. Our Dr Maurau whom all my children will remember and esteem as “the Good” Doctor of Reynella

and my intimate friend for many years, was then a nice bashful young man, just married and only just passed as a

Surgeon, was as I have said, sent to assure us that the man had died of English Cholera. Among the many indignant

denials made, I who saw the point of a joke said, Dr I will prove to you, and you shall acknowledge that you are

wrong. Well said he if you put your opinion before that of the Health Officers I have no more to Say. Nay said I,

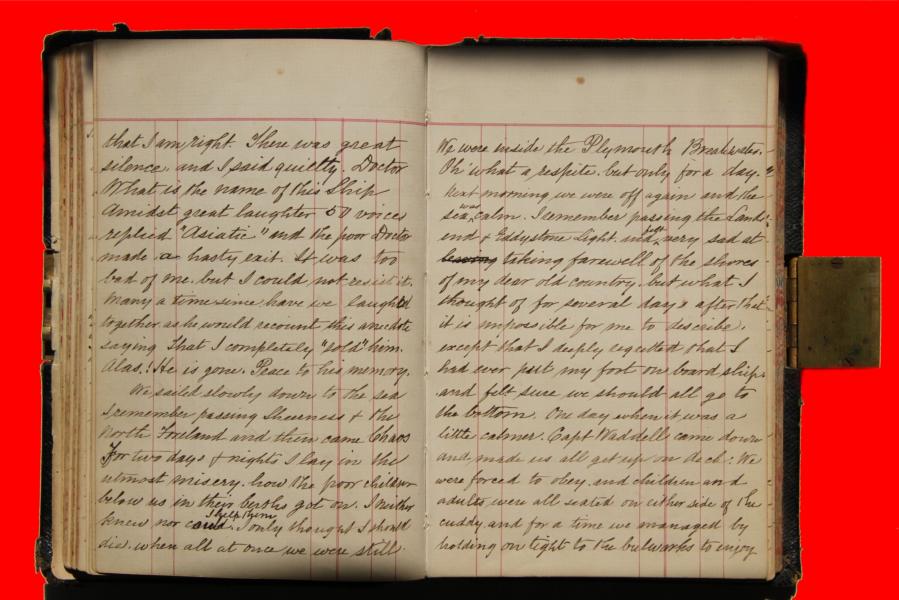

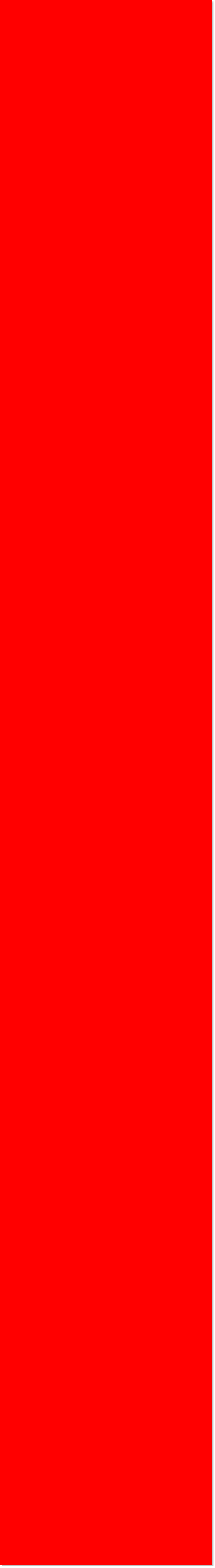

but you shall acknowledge that I am right. There was great silence, and I said quietly, Doctor, What is the name of

this ship. Amidst great laughter 50 voices replied “Asiatic” and the poor Dr made a hasty exit. It was too bad of me,

but I could not resist it, many a time since have we laughed together as he would recount this anecdote saying;

That I completely "sold" him. Alas! He is gone. Peace to his memory.

We sailed slowly down to the sea I remember passing Sheerness and the North Foreland and then came Chaos.

For two days and nights I lay in the utmost misery, how the poor children below us in their berths got on, I neither

knew nor could I help them I only thought I should die, when all at once we were still. We were inside the Plymouth

Breakwater, Oh what a respite, but only for a day. Next morning we were off again and the sea was calm, I

remember passing the Landsend and Eddystone Light, and felt very sad at taking farewell of the shores of my dear

old country, but what I thought of for several days after that it is impossible for me to describe, except that I deeply

regretted that I had ever put my foot on board ship, and felt sure we should all go to the bottom.

One day when it was a little calmer, Capt Waddell came down and made us all get up on deck. We were forced to

obey, and children and adults were all seated on either side of the cuddy and for a time we managed by holding on

tight to the bulwarks to enjoy in some measure the rays of the sun but it was of brief duration for the sky soon

clouded, the wind arose, a tremendous sea struck the vessel, and your Mother who sat on the opposite side from

me was sent spinning right across the ship down to me, and we all had to be assisted by the sailors down to our

bunks. A day or two more of misery, and then the Captain told us that we had crossed the Bay of Biscay and should

soon have calmer sailing.

This prediction proved correct, and getting more used to the ship and its ways we gradually found ourselves

more comfortable. But your mother could not relish the food allowed us nor did the children, and poor mother

often went hungry and longed for some more flour especially as she could not eat the ship's biscuits which they

ironically called bread, only a small quantity of flour being doled out to us which chiefly went for the children.

But we could not buy it, and so had to put up without it. As for myself, after I got over the sickness, I felt better

than I had been in England but still far from well and did not relish the food any more than the others.

On the next Sunday we had service on board. Passengers crew and all not engaged working the ship were

arranged around the cuddy, and the Rev Mr Cheetham a Congregational Minister who with his wife and family

were Steerage passengers with us, conducted the service which we greatly enjoyed. After dinner the first mate

announced that we were passing Teneriffe, and must look out for the Peak. We looked and looked in vain no sign

of land could we see, when all at once I looked above the white fleecy clouds which bounded the horizon and there

high above the clouds, in the pure blue ether, arose the Peak in all its magnificent grandeur. Its height, I think is

15,000 feet.

A few days after this we were becalmed and as we were getting into the tropics and nearing the equator the heat

became very great, while the fact of our being becalmed, and the offal of the ship lying all round about us caused

a stench to fill the ship almost unendurable. We were becalmed a fortnight and our [sic] became most distressing.

On the 5th October however things came to a climax in more than one respect. Your Mother was taken poorly in

the evening, and the Dr ordered her into the Hospital, which was hastily prepared for her and before midnight she

was safely delivered of our fourth daughter, Annie Oceana, now Mrs G W Padman. In the early morning while I

was sitting on the gangway steps talking with the Doctor’s Assistant, I exclaimed "The Ship's moving," Nonsense

said he, but I ran to the bulwarks, and sure enough she was going nicely thro' the water at two or three miles an

hour. Oh what a double relief. The birth of our child was entered in the ship's log as having occurred in lat. 6.35 N

and long. W 6 1/2 degrees North of the equator.

Crossing the Line.

Two days afterwards we were told that we should cross the line that evening, and a fat old cornishman on board

was very anxious to see the ship go over it, as he thought it was a veritable line or rope, so the first mate determined

to gratify him. We agreed that he should be awoke in the night, and scolded because he had not got up before we

had passed it, which the mate informed us we had done an hour before. The old man rudely awaked hurried on

deck his shirt tail floating in the wind, and exclaiming in true Cornish style. Where is her! I can't see her! 0h what

a pity! The mate said don't you [sic] that line pointing to a streak on the horizon. But the old man was not to be

gulled. "Her baint She” he said, "You be gammoning I." Well said the mate I'll convince you, and fetching his

telescope, he adroitly put a hair across the sight, and handed it to him. Amid roars of laughter the old man cried

out "There she be" "I see her" "Thankee Mr Metcalf" “I said home that I would see the line, and now I have seen

her" and went to his bunk quite satisfied.

When your Mother had been in the Hospital about 3 days the Captn. ordered the Medical comforts to be stopped

as she was doing well. I thought it very cruel, but there was no appeal, but when I saw her pining for want of proper

nourishment I was very indignant. Now all the money we possessed was 5 sovereigns which Mother had sewed

between the bones of her stays. So I said Mother, give me your stays but she refused, however I soon got them and

ripped out one, and got a bottle of Port Wine for her. Cost 5/-. She afterwards had another bottle and so she sewed

up the others and we arrived in Adelaide with £4-10-0 and 5 children. We had hoped to have had one sovereign for

each child.

We had by this time become used to the ship and sometimes greatly enjoyed ourselves when the weather was

calm and the sea moderate. For myself I felt so well and my appetite was so good that I could relish to the full the

coarse food provided. While your Mother was in the Hospital, I had of course the care of the children and had

enough to do, especially as our little Boy Joseph was very poorly and had a large boil or ulcer formed in his back

which required constant attention. The heat too being in the tropics was dreadful. It was then that I began to

experience a complete change in my physical nature. I began to perspire a thing I had never done before and so

freely that the bed would be almost wet through in the morning and had to be placed on the bulwarks to dry.

New found health.

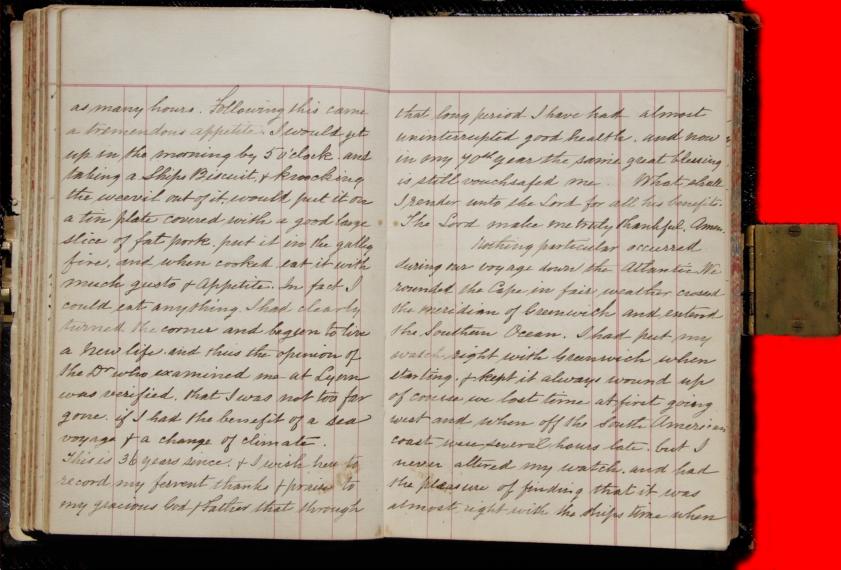

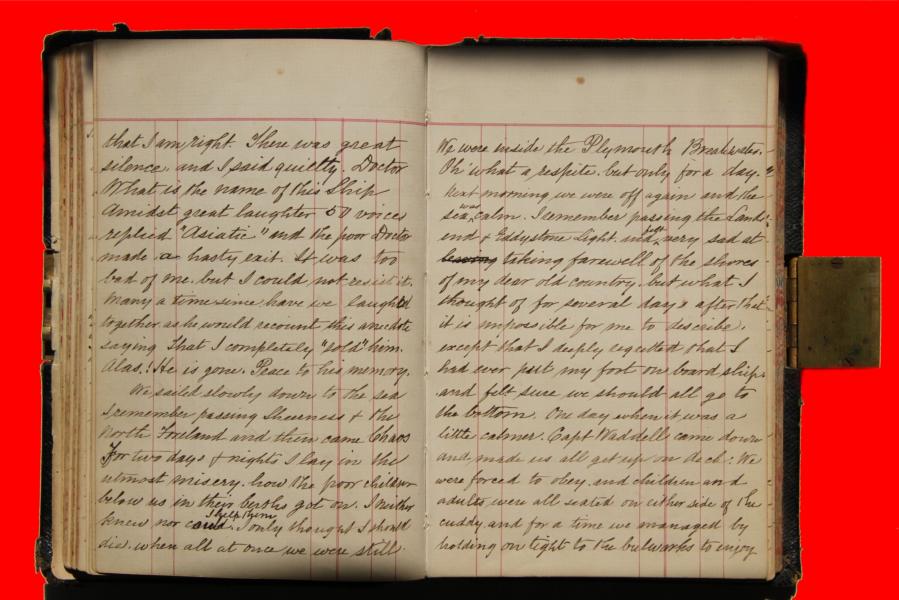

My skin too, which had always been dry and hard like chicken flesh changed by degrees into a fair and clear skin

like that of a little child. It seemed as if I had done all the sweating of 33 years in almost as many hours.

Following this came a tremendous appetite, I would get up in the morning by 5 o'clock, and taking a Ship's Biscuit,

and knocking the weevil out of it, would put it on a tin plate covered with a good large slice of fat pork, put it in the

galley fire, and when cooked eat it with much gusto and Appetite. In fact I could eat anything, I had clearly turned

the corner and begun to live a new life, and thus the opinion of the Dr who examined me at Lynn was verified, that

I was not too far gone, if I had the benefit of a sea voyage and a change of climate.

This is 36 years since and I wish here to record my fervent thanks and praise to my gracious God and Father that

through that long period, I have had almost uninterrupted good health, and now in my 70th year the same great

blessing is still vouchsafed me. What shall I render unto the Lord for all his benefits. The Lord make me truly

thankful, Amen.

Nothing particular occurred during our voyage down the Atlantic. We rounded the Cape in fair weather crossed

the meridian of Greenwich and entered the Southern Ocean. I had put my watch right with Greenwich when

starting, and kept it always wound up of course we lost time at first going west and when off the South American

coast were several hours late, but I never altered my watch, and had the pleasure of finding, that it was almost right

with the ship's time when we crossed the first meridian. Then going East we began to gain time, till on arrival

at the Port I found my watch 9 1/2 hours late. But I am forestalling. We had made very slow progress going down

the Atlantic, but when we entered the Southern Ocean we had fine westerly and southerly winds and went on gaily.

Our old tub of a ship which foundered going home at Port Elizabeth in South Africa behaved nobly. Our baby

Oceana was getting on finely, a fat chubby infant, and our first mate Mr Metcalf, would often ask your Mother to

be allowed to nurse it. He said he had a family of his own in London. He would take the baby round among the

passengers and have a sly hit at some of the newly married women, among whom there had been two or three

failures on the voyage, saying "Ah! this is a really baby, none of your make believes." Your Mother too was much

better as were the children, and we were now all looking anxiously for the first sight of the New Country.

We passed within sight of St Paul where the Captain had promised to call for water, but when we sighted it resolved

not to lose any time, so we did not call.

It was on the 24th Decr we caught sight of Kangaroo Island, and the Captain promised us, that we should have

roast beef and plum pudding at Adelaide on Christmas day if we found it ourselves but we were doomed to

disappointment. On Christmas morning we entered the Gulf but were opposed by a very strong wind from the

North which we found afterwards was a hot wind. All that day we did nothing but tack from side to side making

but little or no progress. We saw "the goodly land and Lebanon" the Southern coast looked particularly inviting,

but could not enter it, and so, instead of dining on Christmas fare, we were doomed to regale ourselves on the

inevitable salt hunk. It was not till noon of the next day that we got to the Light Ship and there we found the

"Harry Lorregner" a fine new emigrant ship that had left London a month after us. Mr Timmins and Wife of

Nairne came out in her.

We did not arrive at the Port after all till evening but most of the male passengers went off to Adelaide at once.

I did not, I and Miss Griffin whom I have not mentioned before, went on shore, and walked as far as Alberton a

township about a mile or so from the Port, to see how we liked the new land. This young lady was an assistant in a

Drapers Shop in Lynn, and a Singer in the Congregational Chapel like myself. When she heard that I was going to

Adelaide she asked me only the Sunday before we sailed whether she could go out under our protection in the

single women's department. We agreed, and tho' she had only a few days to prepare, she was ready and went with

us on Thursday and sailed with us, not even going to see her aged parents, who lived in Hampshire, because there

was no time. I may here at once say that she got a situation as Governess in the family of the Hon W Duffield of

Gawler, and as that Gentleman got rich very fast their household became large, and she became Housekeeper and

General Manager of the household, entrusted her savings in the Mr Duffield's hands and in 15 years time saved

money enough to go home to England and to keep herself respectably but now I hear that she has been for years

past out here again, and is living at Mitcham.

Adelaide - a new life.

The next morning Miss Griffin and I started for Adelaide to seek our fortunes. The day was very hot and the sun

scorching. Our first visit was to Mr Geo Rolfe the only friend we knew in Adelaide who was one of the Deacons of

our Church in Lynn and who had emigrated about six months before we did, with his wife and two children.

He was a Draper in Lynn but had been insolvent, and all his available cash I was informed was about £100.

They had a most unfortunate voyage, lasting 6 1/2 months, and were nearly starved causing Mrs Rolfe to be

seriously ill and she died within a few weeks of landing. We found Mr Rolfe in business as a Land Agent, and doing

well. He was cousin to Mr Jno Morphett now Sir John a rich landowner, who doubtless put him into business.

He received us very kindly, but was very busy so we did not trouble him long. He asked me what I intended to do.

I said of course, school teaching was my profession. Oh! said he That is but poor work, Adelaide is full of little

schools and when a person can get nothing else to do they start teaching. What else can you do. Well said I,

I could fulfil the duties of a Clerk. Said he That is much worse the city is deluged with clerks of all sorts.

Can you do anything else? I said I could work at my trade of a tailor. Why said he, That is worst of all. This was

poor encouragement. But said he don't be dismayed, something will turn up in a few days.

Bring your wife and family to my House, we will manage to do somehow, and as tomorrow is Saturday, you can

sleep there on Saturday night and on Sunday I will introduce you to some friends who will be able to help you.

We then left him. In the afternoon we walked to Kensington to see old Mr Roberts, to whom I had a letter of

introduction from my brother Thomas who was on the Committee of my brother's School at Wem Shropshire

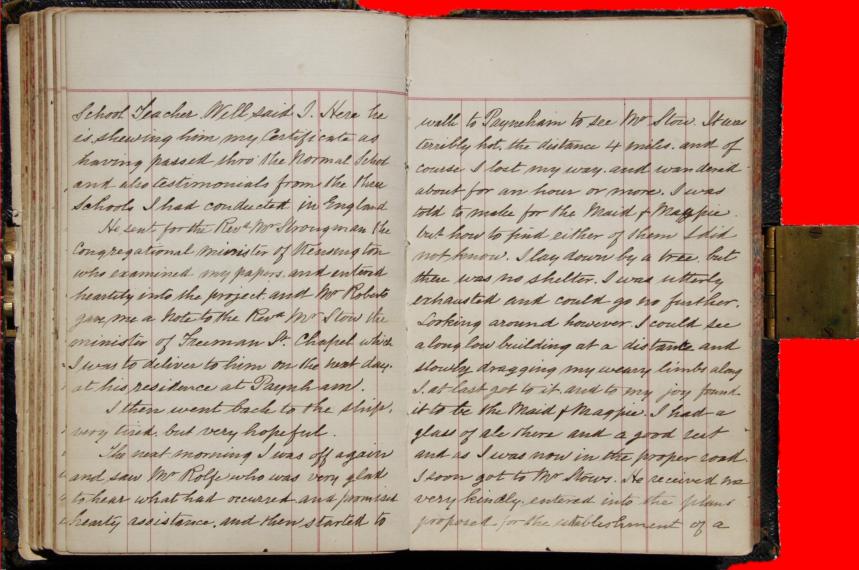

and reputed very rich. He received me very coolly, I thought, but when he opened the letter his manner changed.

Why said he, Have you got any testimonials as to your fitness as a teacher. If so, you are the very man we have been

looking for. We want to establish a Day School in connection with Freeman St Chapel but we will not do it until

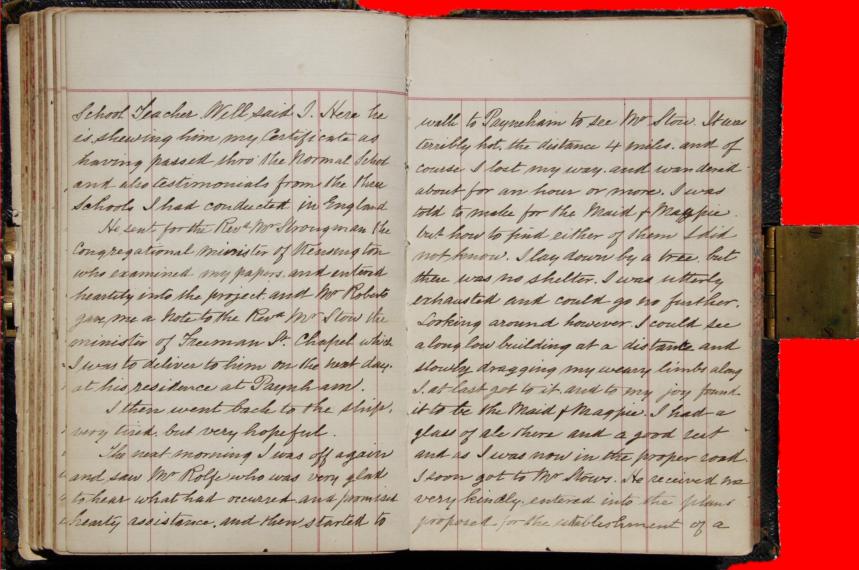

we can find a regularly certificated British School Teacher. Well said I. Here he is shewing him my Certificate as

having passed through the Normal School and also testimonials from the three schools I had conducted in England.

He sent for the Rev Mr Strongman, the Congregational Minister of Kensington who examined my papers, and

entered heartily into the project, and Mr Roberts gave me a note to the Rev Mr Stow the Minister of Freeman St

Chapel which I was to deliver to him on the next day, at his residence at Paynham[sic].

Job search.

I then went back to the ship, very tired, but very hopeful. The next morning I was off again and saw Mr Rolfe who

was very glad to hear what had occurred and promised hearty assistance, and then started to walk to Payneham to

see Mr Stow. It was terribly hot, the distance 4 miles, and of course I lost my way, and wandered about for an hour

or more. I was told to make for the Maid and Magpie, but how to find either of them I did not know. I lay down by

a tree, but there was no shelter, I was utterly exhausted and could go no further. Looking around however, I could

see a long low building at a distance and slowly dragging my weary limbs along I at last got to it and to my joy found

it to be the Maid and Magpie. I had a glass of Ale there and a good rest and as I was now in the proper road, I soon

got to Mr Stow's. He received me very kindly, entered into the plans proposed for the establishment of a School

and after having dinner and tea I walked back to town. An awful dust storm with loud thunder and vivid lightning

met me on my way, and presently the rain poured down so fiercely that I was drenched in a minute. I never had

seen such a rain before. I kept on my way much frightened and wet through, and by the time I reached town the

rain had ceased, and the sky cleared and the cool west wind was very refreshing. I again went back to the ship.

On Sunday, I went again to town to Mr Rolfe's, and with him to Freeman St Chapel, and heard Mr Stow, and

thought him one of the best preachers I had ever heard. Mr Rolfe introduced me to the people and a notice was

read calling a meeting of all interested in commencing a British Day School in connection with the Chapel for

Monday eve. At that meeting a Committee was formed, and I was appointed Teacher, School to begin on the

following Monday in the S. School Room at the back of the Chapel. I was to have no payment from the Committee

but they were to spend a few pounds in fitting up the school, and I was to have the school fees which were fixed at

1/- per week each except for little children under 7, at, I think 8d per week. That night I went back to the Ship

happy and thankful for my succefs.

On Tuesday mg I brought your Mother, my 5 children and all, my household gods[sic] up in a Bullock dray

to Mr Rolfe's at North Adelaide for a day or so while I was looking for a house, and finding that Mr Roberts had a

house to let at Kensington, we took it and removed there the next day. It had only two rooms with brick floor, but

the rent was low and we had no furniture of any value to put into it and so it suited us very well. I borrowed some

forms from the Congregational S. School to form a bed-stead for the children and two seats with backs from the

Chapel made a first rate bed-stead for ourselves, we had small boxes for chairs and a large one for table and so, as

our finances were running low, we did not spend any upon furniture.

I commenced school on Monday with about 50 scholars a very good beginning and was busy enough all the

week organising and getting things in order. I walked from Kensington every morning with my two eldest girls,

Mary and Susanna whom I found very useful in the school. Mary being over 10 and Susanna over 8 years of age.

In less than a month my school was over 80 strong and I had quite enough to do. In about 3 months I found a

reaction setting in. The parents complained that there was no female to teach sewing and I lost several girls in

consequence. I laid the matter before the Committee and requested a female assistant which after a deal of

pressing they allowed me, and appointed Miss Sootheran now Mrs Crossley, late of Virginia now of Ararat

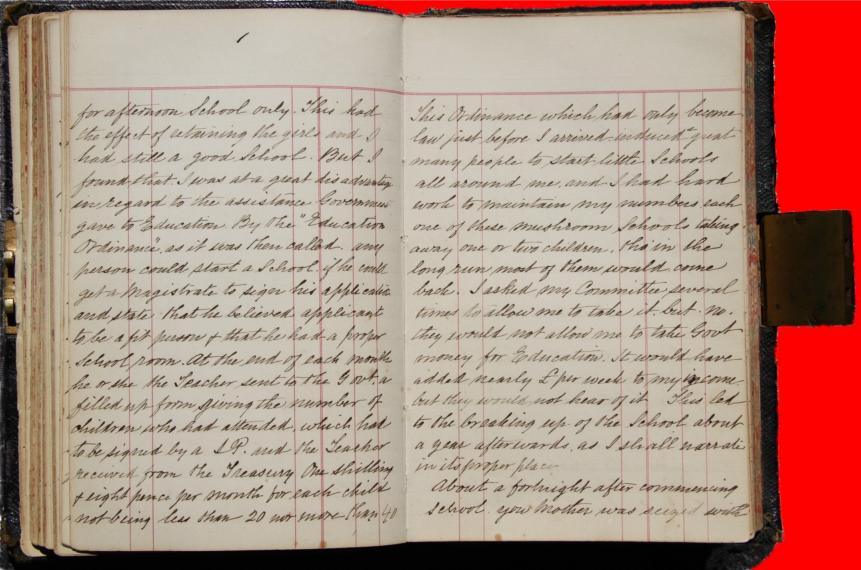

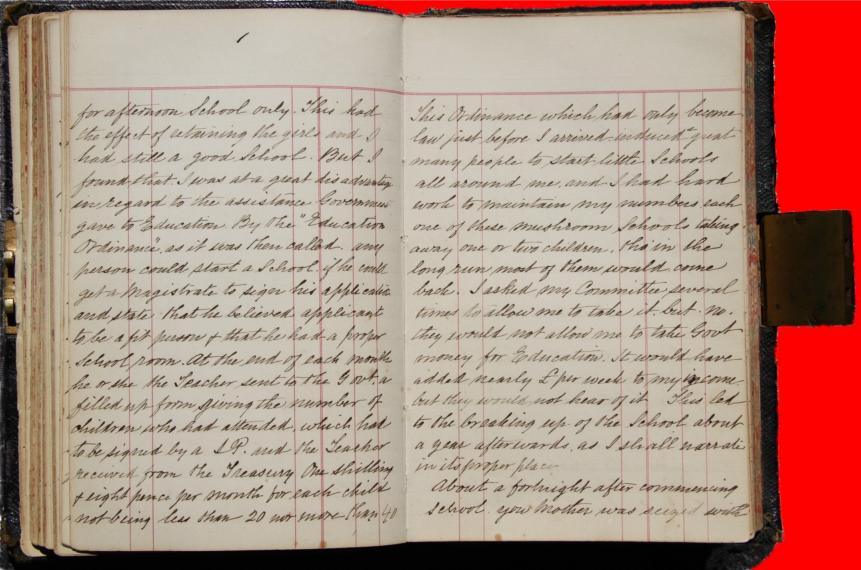

Victoria for afternoon school only. This had the effect of retaining the girls and I had still a good school.

But I found that I was at a great disadvantage in regard to the assistance Government gave to Education,

by the "Education Ordinance" as it was then called.

Any person could start a school if he could get a Magistrate to sign his application and state that he believed

applicant to be a fit person and that he had a proper school room. At the end of each month he or she the Teacher

sent to the Govt a filled up form giving the number of children who had attended, which had to be signed by a J.P.,

and the Teacher received from the Treasury One Shilling and eight pence per month for each child not being less

than 20 nor more than 40. This Ordinance which had only become law just before I arrived induced a great many

people to start little schools all around me and I had hard work to maintain my numbers, each one of these

mushroom schools taking away one or two children, tho' in the long run most of them would come back.

THE LOCKED JOURNAL

Page 4.

Before I go on to describe the incidents of the voyage, I must narrate a laughable story, in which I played a very

wicked part. Our Dr Maurau whom all my children will remember and esteem as “the Good” Doctor of Reynella

and my intimate friend for many years, was then a nice bashful young man, just married and only just passed as a

Surgeon, was as I have said, sent to assure us that the man had died of English Cholera. Among the many indignant

denials made, I who saw the point of a joke said, Dr I will prove to you, and you shall acknowledge that you are

wrong. Well said he if you put your opinion before that of the Health Officers I have no more to Say. Nay said I,

but you shall acknowledge that I am right. There was great silence, and I said quietly, Doctor, What is the name of

this ship. Amidst great laughter 50 voices replied “Asiatic” and the poor Dr made a hasty exit. It was too bad of me,

but I could not resist it, many a time since have we laughed together as he would recount this anecdote saying;

That I completely "sold" him. Alas! He is gone. Peace to his memory.

We sailed slowly down to the sea I remember passing Sheerness and the North Foreland and then came Chaos.

For two days and nights I lay in the utmost misery, how the poor children below us in their berths got on, I neither

knew nor could I help them I only thought I should die, when all at once we were still. We were inside the Plymouth

Breakwater, Oh what a respite, but only for a day. Next morning we were off again and the sea was calm, I

remember passing the Landsend and Eddystone Light, and felt very sad at taking farewell of the shores of my dear

old country, but what I thought of for several days after that it is impossible for me to describe, except that I deeply

regretted that I had ever put my foot on board ship, and felt sure we should all go to the bottom.

One day when it was a little calmer, Capt Waddell came down and made us all get up on deck. We were forced to

obey, and children and adults were all seated on either side of the cuddy and for a time we managed by holding on

tight to the bulwarks to enjoy in some measure the rays of the sun but it was of brief duration for the sky soon

clouded, the wind arose, a tremendous sea struck the vessel, and your Mother who sat on the opposite side from

me was sent spinning right across the ship down to me, and we all had to be assisted by the sailors down to our

bunks. A day or two more of misery, and then the Captain told us that we had crossed the Bay of Biscay and should

soon have calmer sailing.

This prediction proved correct, and getting more used to the ship and its ways we gradually found ourselves

more comfortable. But your mother could not relish the food allowed us nor did the children, and poor mother

often went hungry and longed for some more flour especially as she could not eat the ship's biscuits which they

ironically called bread, only a small quantity of flour being doled out to us which chiefly went for the children.

But we could not buy it, and so had to put up without it. As for myself, after I got over the sickness, I felt better

than I had been in England but still far from well and did not relish the food any more than the others.

On the next Sunday we had service on board. Passengers crew and all not engaged working the ship were

arranged around the cuddy, and the Rev Mr Cheetham a Congregational Minister who with his wife and family

were Steerage passengers with us, conducted the service which we greatly enjoyed. After dinner the first mate

announced that we were passing Teneriffe, and must look out for the Peak. We looked and looked in vain no sign

of land could we see, when all at once I looked above the white fleecy clouds which bounded the horizon and there

high above the clouds, in the pure blue ether, arose the Peak in all its magnificent grandeur. Its height, I think is

15,000 feet.

A few days after this we were becalmed and as we were getting into the tropics and nearing the equator the heat

became very great, while the fact of our being becalmed, and the offal of the ship lying all round about us caused

a stench to fill the ship almost unendurable. We were becalmed a fortnight and our [sic] became most distressing.

On the 5th October however things came to a climax in more than one respect. Your Mother was taken poorly in

the evening, and the Dr ordered her into the Hospital, which was hastily prepared for her and before midnight she

was safely delivered of our fourth daughter, Annie Oceana, now Mrs G W Padman. In the early morning while I

was sitting on the gangway steps talking with the Doctor’s Assistant, I exclaimed "The Ship's moving," Nonsense

said he, but I ran to the bulwarks, and sure enough she was going nicely thro' the water at two or three miles an

hour. Oh what a double relief. The birth of our child was entered in the ship's log as having occurred in lat. 6.35 N

and long. W 6 1/2 degrees North of the equator.

Crossing the Line.

Two days afterwards we were told that we should cross the line that evening, and a fat old cornishman on board

was very anxious to see the ship go over it, as he thought it was a veritable line or rope, so the first mate determined

to gratify him. We agreed that he should be awoke in the night, and scolded because he had not got up before we

had passed it, which the mate informed us we had done an hour before. The old man rudely awaked hurried on

deck his shirt tail floating in the wind, and exclaiming in true Cornish style. Where is her! I can't see her! 0h what

a pity! The mate said don't you [sic] that line pointing to a streak on the horizon. But the old man was not to be

gulled. "Her baint She” he said, "You be gammoning I." Well said the mate I'll convince you, and fetching his

telescope, he adroitly put a hair across the sight, and handed it to him. Amid roars of laughter the old man cried

out "There she be" "I see her" "Thankee Mr Metcalf" “I said home that I would see the line, and now I have seen

her" and went to his bunk quite satisfied.

When your Mother had been in the Hospital about 3 days the Captn. ordered the Medical comforts to be stopped

as she was doing well. I thought it very cruel, but there was no appeal, but when I saw her pining for want of proper

nourishment I was very indignant. Now all the money we possessed was 5 sovereigns which Mother had sewed

between the bones of her stays. So I said Mother, give me your stays but she refused, however I soon got them and

ripped out one, and got a bottle of Port Wine for her. Cost 5/-. She afterwards had another bottle and so she sewed

up the others and we arrived in Adelaide with £4-10-0 and 5 children. We had hoped to have had one sovereign for

each child.

We had by this time become used to the ship and sometimes greatly enjoyed ourselves when the weather was

calm and the sea moderate. For myself I felt so well and my appetite was so good that I could relish to the full the

coarse food provided. While your Mother was in the Hospital, I had of course the care of the children and had

enough to do, especially as our little Boy Joseph was very poorly and had a large boil or ulcer formed in his back

which required constant attention. The heat too being in the tropics was dreadful. It was then that I began to

experience a complete change in my physical nature. I began to perspire a thing I had never done before and so

freely that the bed would be almost wet through in the morning and had to be placed on the bulwarks to dry.

New found health.

My skin too, which had always been dry and hard like chicken flesh changed by degrees into a fair and clear skin

like that of a little child. It seemed as if I had done all the sweating of 33 years in almost as many hours.

Following this came a tremendous appetite, I would get up in the morning by 5 o'clock, and taking a Ship's Biscuit,

and knocking the weevil out of it, would put it on a tin plate covered with a good large slice of fat pork, put it in the

galley fire, and when cooked eat it with much gusto and Appetite. In fact I could eat anything, I had clearly turned

the corner and begun to live a new life, and thus the opinion of the Dr who examined me at Lynn was verified, that

I was not too far gone, if I had the benefit of a sea voyage and a change of climate.

This is 36 years since and I wish here to record my fervent thanks and praise to my gracious God and Father that

through that long period, I have had almost uninterrupted good health, and now in my 70th year the same great

blessing is still vouchsafed me. What shall I render unto the Lord for all his benefits. The Lord make me truly

thankful, Amen.

Nothing particular occurred during our voyage down the Atlantic. We rounded the Cape in fair weather crossed

the meridian of Greenwich and entered the Southern Ocean. I had put my watch right with Greenwich when

starting, and kept it always wound up of course we lost time at first going west and when off the South American

coast were several hours late, but I never altered my watch, and had the pleasure of finding, that it was almost right

with the ship's time when we crossed the first meridian. Then going East we began to gain time, till on arrival

at the Port I found my watch 9 1/2 hours late. But I am forestalling. We had made very slow progress going down

the Atlantic, but when we entered the Southern Ocean we had fine westerly and southerly winds and went on gaily.

Our old tub of a ship which foundered going home at Port Elizabeth in South Africa behaved nobly. Our baby

Oceana was getting on finely, a fat chubby infant, and our first mate Mr Metcalf, would often ask your Mother to

be allowed to nurse it. He said he had a family of his own in London. He would take the baby round among the

passengers and have a sly hit at some of the newly married women, among whom there had been two or three

failures on the voyage, saying "Ah! this is a really baby, none of your make believes." Your Mother too was much

better as were the children, and we were now all looking anxiously for the first sight of the New Country.

We passed within sight of St Paul where the Captain had promised to call for water, but when we sighted it resolved

not to lose any time, so we did not call.

It was on the 24th Decr we caught sight of Kangaroo Island, and the Captain promised us, that we should have

roast beef and plum pudding at Adelaide on Christmas day if we found it ourselves but we were doomed to

disappointment. On Christmas morning we entered the Gulf but were opposed by a very strong wind from the

North which we found afterwards was a hot wind. All that day we did nothing but tack from side to side making

but little or no progress. We saw "the goodly land and Lebanon" the Southern coast looked particularly inviting,

but could not enter it, and so, instead of dining on Christmas fare, we were doomed to regale ourselves on the

inevitable salt hunk. It was not till noon of the next day that we got to the Light Ship and there we found the

"Harry Lorregner" a fine new emigrant ship that had left London a month after us. Mr Timmins and Wife of

Nairne came out in her.

We did not arrive at the Port after all till evening but most of the male passengers went off to Adelaide at once.

I did not, I and Miss Griffin whom I have not mentioned before, went on shore, and walked as far as Alberton a

township about a mile or so from the Port, to see how we liked the new land. This young lady was an assistant in a

Drapers Shop in Lynn, and a Singer in the Congregational Chapel like myself. When she heard that I was going to

Adelaide she asked me only the Sunday before we sailed whether she could go out under our protection in the

single women's department. We agreed, and tho' she had only a few days to prepare, she was ready and went with

us on Thursday and sailed with us, not even going to see her aged parents, who lived in Hampshire, because there

was no time. I may here at once say that she got a situation as Governess in the family of the Hon W Duffield of

Gawler, and as that Gentleman got rich very fast their household became large, and she became Housekeeper and

General Manager of the household, entrusted her savings in the Mr Duffield's hands and in 15 years time saved

money enough to go home to England and to keep herself respectably but now I hear that she has been for years

past out here again, and is living at Mitcham.

Adelaide - a new life.

The next morning Miss Griffin and I started for Adelaide to seek our fortunes. The day was very hot and the sun

scorching. Our first visit was to Mr Geo Rolfe the only friend we knew in Adelaide who was one of the Deacons of

our Church in Lynn and who had emigrated about six months before we did, with his wife and two children.

He was a Draper in Lynn but had been insolvent, and all his available cash I was informed was about £100.

They had a most unfortunate voyage, lasting 6 1/2 months, and were nearly starved causing Mrs Rolfe to be

seriously ill and she died within a few weeks of landing. We found Mr Rolfe in business as a Land Agent, and doing

well. He was cousin to Mr Jno Morphett now Sir John a rich landowner, who doubtless put him into business.

He received us very kindly, but was very busy so we did not trouble him long. He asked me what I intended to do.

I said of course, school teaching was my profession. Oh! said he That is but poor work, Adelaide is full of little

schools and when a person can get nothing else to do they start teaching. What else can you do. Well said I,

I could fulfil the duties of a Clerk. Said he That is much worse the city is deluged with clerks of all sorts.

Can you do anything else? I said I could work at my trade of a tailor. Why said he, That is worst of all. This was

poor encouragement. But said he don't be dismayed, something will turn up in a few days.

Bring your wife and family to my House, we will manage to do somehow, and as tomorrow is Saturday, you can

sleep there on Saturday night and on Sunday I will introduce you to some friends who will be able to help you.

We then left him. In the afternoon we walked to Kensington to see old Mr Roberts, to whom I had a letter of

introduction from my brother Thomas who was on the Committee of my brother's School at Wem Shropshire

and reputed very rich. He received me very coolly, I thought, but when he opened the letter his manner changed.

Why said he, Have you got any testimonials as to your fitness as a teacher. If so, you are the very man we have been

looking for. We want to establish a Day School in connection with Freeman St Chapel but we will not do it until

we can find a regularly certificated British School Teacher. Well said I. Here he is shewing him my Certificate as

having passed through the Normal School and also testimonials from the three schools I had conducted in England.

He sent for the Rev Mr Strongman, the Congregational Minister of Kensington who examined my papers, and

entered heartily into the project, and Mr Roberts gave me a note to the Rev Mr Stow the Minister of Freeman St

Chapel which I was to deliver to him on the next day, at his residence at Paynham[sic].

Job search.

I then went back to the ship, very tired, but very hopeful. The next morning I was off again and saw Mr Rolfe who

was very glad to hear what had occurred and promised hearty assistance, and then started to walk to Payneham to

see Mr Stow. It was terribly hot, the distance 4 miles, and of course I lost my way, and wandered about for an hour

or more. I was told to make for the Maid and Magpie, but how to find either of them I did not know. I lay down by

a tree, but there was no shelter, I was utterly exhausted and could go no further. Looking around however, I could

see a long low building at a distance and slowly dragging my weary limbs along I at last got to it and to my joy found

it to be the Maid and Magpie. I had a glass of Ale there and a good rest and as I was now in the proper road, I soon

got to Mr Stow's. He received me very kindly, entered into the plans proposed for the establishment of a School

and after having dinner and tea I walked back to town. An awful dust storm with loud thunder and vivid lightning

met me on my way, and presently the rain poured down so fiercely that I was drenched in a minute. I never had

seen such a rain before. I kept on my way much frightened and wet through, and by the time I reached town the

rain had ceased, and the sky cleared and the cool west wind was very refreshing. I again went back to the ship.

On Sunday, I went again to town to Mr Rolfe's, and with him to Freeman St Chapel, and heard Mr Stow, and

thought him one of the best preachers I had ever heard. Mr Rolfe introduced me to the people and a notice was

read calling a meeting of all interested in commencing a British Day School in connection with the Chapel for

Monday eve. At that meeting a Committee was formed, and I was appointed Teacher, School to begin on the

following Monday in the S. School Room at the back of the Chapel. I was to have no payment from the Committee

but they were to spend a few pounds in fitting up the school, and I was to have the school fees which were fixed at

1/- per week each except for little children under 7, at, I think 8d per week. That night I went back to the Ship

happy and thankful for my succefs.

On Tuesday mg I brought your Mother, my 5 children and all, my household gods[sic] up in a Bullock dray

to Mr Rolfe's at North Adelaide for a day or so while I was looking for a house, and finding that Mr Roberts had a

house to let at Kensington, we took it and removed there the next day. It had only two rooms with brick floor, but

the rent was low and we had no furniture of any value to put into it and so it suited us very well. I borrowed some

forms from the Congregational S. School to form a bed-stead for the children and two seats with backs from the

Chapel made a first rate bed-stead for ourselves, we had small boxes for chairs and a large one for table and so, as

our finances were running low, we did not spend any upon furniture.

I commenced school on Monday with about 50 scholars a very good beginning and was busy enough all the

week organising and getting things in order. I walked from Kensington every morning with my two eldest girls,

Mary and Susanna whom I found very useful in the school. Mary being over 10 and Susanna over 8 years of age.

In less than a month my school was over 80 strong and I had quite enough to do. In about 3 months I found a

reaction setting in. The parents complained that there was no female to teach sewing and I lost several girls in

consequence. I laid the matter before the Committee and requested a female assistant which after a deal of

pressing they allowed me, and appointed Miss Sootheran now Mrs Crossley, late of Virginia now of Ararat

Victoria for afternoon school only. This had the effect of retaining the girls and I had still a good school.

But I found that I was at a great disadvantage in regard to the assistance Government gave to Education,

by the "Education Ordinance" as it was then called.

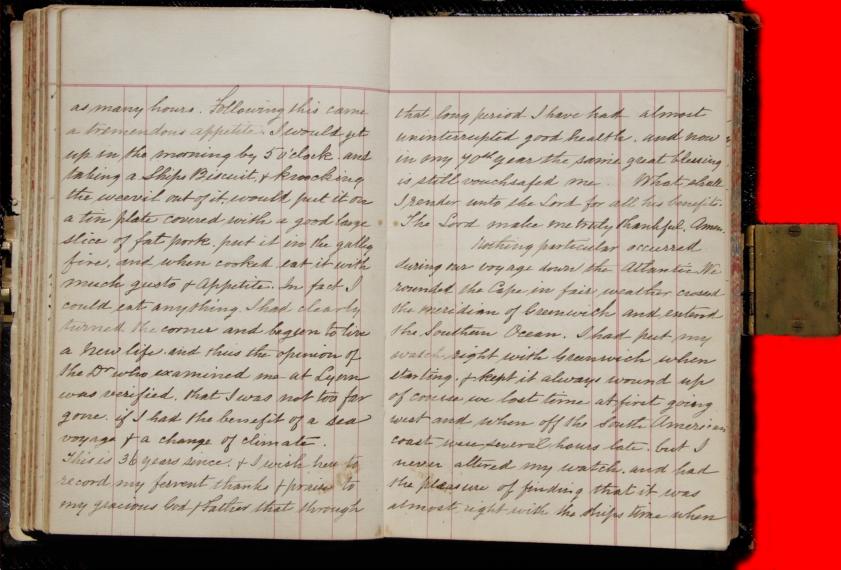

Any person could start a school if he could get a Magistrate to sign his application and state that he believed

applicant to be a fit person and that he had a proper school room. At the end of each month he or she the Teacher

sent to the Govt a filled up form giving the number of children who had attended, which had to be signed by a J.P.,

and the Teacher received from the Treasury One Shilling and eight pence per month for each child not being less

than 20 nor more than 40. This Ordinance which had only become law just before I arrived induced a great many

people to start little schools all around me and I had hard work to maintain my numbers, each one of these

mushroom schools taking away one or two children, tho' in the long run most of them would come back.

The Voyage to South Australia

The Voyage to South Australia

Home Page

Home Page

Home Page

Home Page

THE LOCKED JOURNAL

Page 4.

Before I go on to describe the incidents of the voyage, I must narrate a laughable story, in which I played a very

wicked part. Our Dr Maurau whom all my children will remember and esteem as “the Good” Doctor of Reynella

and my intimate friend for many years, was then a nice bashful young man, just married and only just passed as a

Surgeon, was as I have said, sent to assure us that the man had died of English Cholera. Among the many indignant

denials made, I who saw the point of a joke said, Dr I will prove to you, and you shall acknowledge that you are

wrong. Well said he if you put your opinion before that of the Health Officers I have no more to Say. Nay said I,

but you shall acknowledge that I am right. There was great silence, and I said quietly, Doctor, What is the name of

this ship. Amidst great laughter 50 voices replied “Asiatic” and the poor Dr made a hasty exit. It was too bad of me,

but I could not resist it, many a time since have we laughed together as he would recount this anecdote saying;

That I completely "sold" him. Alas! He is gone. Peace to his memory.

We sailed slowly down to the sea I remember passing Sheerness and the North Foreland and then came Chaos.

For two days and nights I lay in the utmost misery, how the poor children below us in their berths got on, I neither

knew nor could I help them I only thought I should die, when all at once we were still. We were inside the Plymouth

Breakwater, Oh what a respite, but only for a day. Next morning we were off again and the sea was calm, I

remember passing the Landsend and Eddystone Light, and felt very sad at taking farewell of the shores of my dear

old country, but what I thought of for several days after that it is impossible for me to describe, except that I deeply

regretted that I had ever put my foot on board ship, and felt sure we should all go to the bottom.

One day when it was a little calmer, Capt Waddell came down and made us all get up on deck. We were forced to

obey, and children and adults were all seated on either side of the cuddy and for a time we managed by holding on

tight to the bulwarks to enjoy in some measure the rays of the sun but it was of brief duration for the sky soon

clouded, the wind arose, a tremendous sea struck the vessel, and your Mother who sat on the opposite side from

me was sent spinning right across the ship down to me, and we all had to be assisted by the sailors down to our

bunks. A day or two more of misery, and then the Captain told us that we had crossed the Bay of Biscay and should

soon have calmer sailing.

This prediction proved correct, and getting more used to the ship and its ways we gradually found ourselves

more comfortable. But your mother could not relish the food allowed us nor did the children, and poor mother

often went hungry and longed for some more flour especially as she could not eat the ship's biscuits which they

ironically called bread, only a small quantity of flour being doled out to us which chiefly went for the children.

But we could not buy it, and so had to put up without it. As for myself, after I got over the sickness, I felt better

than I had been in England but still far from well and did not relish the food any more than the others.

On the next Sunday we had service on board. Passengers crew and all not engaged working the ship were

arranged around the cuddy, and the Rev Mr Cheetham a Congregational Minister who with his wife and family

were Steerage passengers with us, conducted the service which we greatly enjoyed. After dinner the first mate

announced that we were passing Teneriffe, and must look out for the Peak. We looked and looked in vain no sign

of land could we see, when all at once I looked above the white fleecy clouds which bounded the horizon and there

high above the clouds, in the pure blue ether, arose the Peak in all its magnificent grandeur. Its height, I think is

15,000 feet.

A few days after this we were becalmed and as we were getting into the tropics and nearing the equator the heat

became very great, while the fact of our being becalmed, and the offal of the ship lying all round about us caused

a stench to fill the ship almost unendurable. We were becalmed a fortnight and our [sic] became most distressing.

On the 5th October however things came to a climax in more than one respect. Your Mother was taken poorly in

the evening, and the Dr ordered her into the Hospital, which was hastily prepared for her and before midnight she

was safely delivered of our fourth daughter, Annie Oceana, now Mrs G W Padman. In the early morning while I

was sitting on the gangway steps talking with the Doctor’s Assistant, I exclaimed "The Ship's moving," Nonsense

said he, but I ran to the bulwarks, and sure enough she was going nicely thro' the water at two or three miles an

hour. Oh what a double relief. The birth of our child was entered in the ship's log as having occurred in lat. 6.35 N

and long. W 6 1/2 degrees North of the equator.

Crossing the Line.

Two days afterwards we were told that we should cross the line that evening, and a fat old cornishman on board

was very anxious to see the ship go over it, as he thought it was a veritable line or rope, so the first mate determined

to gratify him. We agreed that he should be awoke in the night, and scolded because he had not got up before we

had passed it, which the mate informed us we had done an hour before. The old man rudely awaked hurried on

deck his shirt tail floating in the wind, and exclaiming in true Cornish style. Where is her! I can't see her! 0h what

a pity! The mate said don't you [sic] that line pointing to a streak on the horizon. But the old man was not to be

gulled. "Her baint She” he said, "You be gammoning I." Well said the mate I'll convince you, and fetching his

telescope, he adroitly put a hair across the sight, and handed it to him. Amid roars of laughter the old man cried

out "There she be" "I see her" "Thankee Mr Metcalf" “I said home that I would see the line, and now I have seen

her" and went to his bunk quite satisfied.

When your Mother had been in the Hospital about 3 days the Captn. ordered the Medical comforts to be stopped

as she was doing well. I thought it very cruel, but there was no appeal, but when I saw her pining for want of proper

nourishment I was very indignant. Now all the money we possessed was 5 sovereigns which Mother had sewed

between the bones of her stays. So I said Mother, give me your stays but she refused, however I soon got them and

ripped out one, and got a bottle of Port Wine for her. Cost 5/-. She afterwards had another bottle and so she sewed

up the others and we arrived in Adelaide with £4-10-0 and 5 children. We had hoped to have had one sovereign for

each child.

We had by this time become used to the ship and sometimes greatly enjoyed ourselves when the weather was

calm and the sea moderate. For myself I felt so well and my appetite was so good that I could relish to the full the

coarse food provided. While your Mother was in the Hospital, I had of course the care of the children and had

enough to do, especially as our little Boy Joseph was very poorly and had a large boil or ulcer formed in his back

which required constant attention. The heat too being in the tropics was dreadful. It was then that I began to

experience a complete change in my physical nature. I began to perspire a thing I had never done before and so

freely that the bed would be almost wet through in the morning and had to be placed on the bulwarks to dry.

New found health.

My skin too, which had always been dry and hard like chicken flesh changed by degrees into a fair and clear skin

like that of a little child. It seemed as if I had done all the sweating of 33 years in almost as many hours.

Following this came a tremendous appetite, I would get up in the morning by 5 o'clock, and taking a Ship's Biscuit,

and knocking the weevil out of it, would put it on a tin plate covered with a good large slice of fat pork, put it in the

galley fire, and when cooked eat it with much gusto and Appetite. In fact I could eat anything, I had clearly turned

the corner and begun to live a new life, and thus the opinion of the Dr who examined me at Lynn was verified, that

I was not too far gone, if I had the benefit of a sea voyage and a change of climate.

This is 36 years since and I wish here to record my fervent thanks and praise to my gracious God and Father that

through that long period, I have had almost uninterrupted good health, and now in my 70th year the same great

blessing is still vouchsafed me. What shall I render unto the Lord for all his benefits. The Lord make me truly

thankful, Amen.

Nothing particular occurred during our voyage down the Atlantic. We rounded the Cape in fair weather crossed

the meridian of Greenwich and entered the Southern Ocean. I had put my watch right with Greenwich when

starting, and kept it always wound up of course we lost time at first going west and when off the South American

coast were several hours late, but I never altered my watch, and had the pleasure of finding, that it was almost right

with the ship's time when we crossed the first meridian. Then going East we began to gain time, till on arrival

at the Port I found my watch 9 1/2 hours late. But I am forestalling. We had made very slow progress going down

the Atlantic, but when we entered the Southern Ocean we had fine westerly and southerly winds and went on gaily.

Our old tub of a ship which foundered going home at Port Elizabeth in South Africa behaved nobly. Our baby

Oceana was getting on finely, a fat chubby infant, and our first mate Mr Metcalf, would often ask your Mother to

be allowed to nurse it. He said he had a family of his own in London. He would take the baby round among the

passengers and have a sly hit at some of the newly married women, among whom there had been two or three

failures on the voyage, saying "Ah! this is a really baby, none of your make believes." Your Mother too was much

better as were the children, and we were now all looking anxiously for the first sight of the New Country.

We passed within sight of St Paul where the Captain had promised to call for water, but when we sighted it resolved

not to lose any time, so we did not call.

It was on the 24th Decr we caught sight of Kangaroo Island, and the Captain promised us, that we should have

roast beef and plum pudding at Adelaide on Christmas day if we found it ourselves but we were doomed to

disappointment. On Christmas morning we entered the Gulf but were opposed by a very strong wind from the

North which we found afterwards was a hot wind. All that day we did nothing but tack from side to side making

but little or no progress. We saw "the goodly land and Lebanon" the Southern coast looked particularly inviting,

but could not enter it, and so, instead of dining on Christmas fare, we were doomed to regale ourselves on the

inevitable salt hunk. It was not till noon of the next day that we got to the Light Ship and there we found the

"Harry Lorregner" a fine new emigrant ship that had left London a month after us. Mr Timmins and Wife of

Nairne came out in her.

We did not arrive at the Port after all till evening but most of the male passengers went off to Adelaide at once.

I did not, I and Miss Griffin whom I have not mentioned before, went on shore, and walked as far as Alberton a

township about a mile or so from the Port, to see how we liked the new land. This young lady was an assistant in a

Drapers Shop in Lynn, and a Singer in the Congregational Chapel like myself. When she heard that I was going to

Adelaide she asked me only the Sunday before we sailed whether she could go out under our protection in the

single women's department. We agreed, and tho' she had only a few days to prepare, she was ready and went with

us on Thursday and sailed with us, not even going to see her aged parents, who lived in Hampshire, because there

was no time. I may here at once say that she got a situation as Governess in the family of the Hon W Duffield of

Gawler, and as that Gentleman got rich very fast their household became large, and she became Housekeeper and

General Manager of the household, entrusted her savings in the Mr Duffield's hands and in 15 years time saved

money enough to go home to England and to keep herself respectably but now I hear that she has been for years

past out here again, and is living at Mitcham.

Adelaide - a new life.

The next morning Miss Griffin and I started for Adelaide to seek our fortunes. The day was very hot and the sun

scorching. Our first visit was to Mr Geo Rolfe the only friend we knew in Adelaide who was one of the Deacons of

our Church in Lynn and who had emigrated about six months before we did, with his wife and two children.

He was a Draper in Lynn but had been insolvent, and all his available cash I was informed was about £100.

They had a most unfortunate voyage, lasting 6 1/2 months, and were nearly starved causing Mrs Rolfe to be

seriously ill and she died within a few weeks of landing. We found Mr Rolfe in business as a Land Agent, and doing

well. He was cousin to Mr Jno Morphett now Sir John a rich landowner, who doubtless put him into business.

He received us very kindly, but was very busy so we did not trouble him long. He asked me what I intended to do.

I said of course, school teaching was my profession. Oh! said he That is but poor work, Adelaide is full of little

schools and when a person can get nothing else to do they start teaching. What else can you do. Well said I,

I could fulfil the duties of a Clerk. Said he That is much worse the city is deluged with clerks of all sorts.

Can you do anything else? I said I could work at my trade of a tailor. Why said he, That is worst of all. This was

poor encouragement. But said he don't be dismayed, something will turn up in a few days.

Bring your wife and family to my House, we will manage to do somehow, and as tomorrow is Saturday, you can

sleep there on Saturday night and on Sunday I will introduce you to some friends who will be able to help you.

We then left him. In the afternoon we walked to Kensington to see old Mr Roberts, to whom I had a letter of

introduction from my brother Thomas who was on the Committee of my brother's School at Wem Shropshire

and reputed very rich. He received me very coolly, I thought, but when he opened the letter his manner changed.

Why said he, Have you got any testimonials as to your fitness as a teacher. If so, you are the very man we have been

looking for. We want to establish a Day School in connection with Freeman St Chapel but we will not do it until

we can find a regularly certificated British School Teacher. Well said I. Here he is shewing him my Certificate as

having passed through the Normal School and also testimonials from the three schools I had conducted in England.

He sent for the Rev Mr Strongman, the Congregational Minister of Kensington who examined my papers, and

entered heartily into the project, and Mr Roberts gave me a note to the Rev Mr Stow the Minister of Freeman St

Chapel which I was to deliver to him on the next day, at his residence at Paynham[sic].

Job search.

I then went back to the ship, very tired, but very hopeful. The next morning I was off again and saw Mr Rolfe who

was very glad to hear what had occurred and promised hearty assistance, and then started to walk to Payneham to

see Mr Stow. It was terribly hot, the distance 4 miles, and of course I lost my way, and wandered about for an hour

or more. I was told to make for the Maid and Magpie, but how to find either of them I did not know. I lay down by

a tree, but there was no shelter, I was utterly exhausted and could go no further. Looking around however, I could

see a long low building at a distance and slowly dragging my weary limbs along I at last got to it and to my joy found

it to be the Maid and Magpie. I had a glass of Ale there and a good rest and as I was now in the proper road, I soon

got to Mr Stow's. He received me very kindly, entered into the plans proposed for the establishment of a School

and after having dinner and tea I walked back to town. An awful dust storm with loud thunder and vivid lightning

met me on my way, and presently the rain poured down so fiercely that I was drenched in a minute. I never had

seen such a rain before. I kept on my way much frightened and wet through, and by the time I reached town the

rain had ceased, and the sky cleared and the cool west wind was very refreshing. I again went back to the ship.

On Sunday, I went again to town to Mr Rolfe's, and with him to Freeman St Chapel, and heard Mr Stow, and

thought him one of the best preachers I had ever heard. Mr Rolfe introduced me to the people and a notice was

read calling a meeting of all interested in commencing a British Day School in connection with the Chapel for

Monday eve. At that meeting a Committee was formed, and I was appointed Teacher, School to begin on the

following Monday in the S. School Room at the back of the Chapel. I was to have no payment from the Committee

but they were to spend a few pounds in fitting up the school, and I was to have the school fees which were fixed at

1/- per week each except for little children under 7, at, I think 8d per week. That night I went back to the Ship

happy and thankful for my succefs.

On Tuesday mg I brought your Mother, my 5 children and all, my household gods[sic] up in a Bullock dray

to Mr Rolfe's at North Adelaide for a day or so while I was looking for a house, and finding that Mr Roberts had a

house to let at Kensington, we took it and removed there the next day. It had only two rooms with brick floor, but

the rent was low and we had no furniture of any value to put into it and so it suited us very well. I borrowed some

forms from the Congregational S. School to form a bed-stead for the children and two seats with backs from the

Chapel made a first rate bed-stead for ourselves, we had small boxes for chairs and a large one for table and so, as

our finances were running low, we did not spend any upon furniture.

I commenced school on Monday with about 50 scholars a very good beginning and was busy enough all the

week organising and getting things in order. I walked from Kensington every morning with my two eldest girls,

Mary and Susanna whom I found very useful in the school. Mary being over 10 and Susanna over 8 years of age.

In less than a month my school was over 80 strong and I had quite enough to do. In about 3 months I found a

reaction setting in. The parents complained that there was no female to teach sewing and I lost several girls in

consequence. I laid the matter before the Committee and requested a female assistant which after a deal of

pressing they allowed me, and appointed Miss Sootheran now Mrs Crossley, late of Virginia now of Ararat

Victoria for afternoon school only. This had the effect of retaining the girls and I had still a good school.

But I found that I was at a great disadvantage in regard to the assistance Government gave to Education,

by the "Education Ordinance" as it was then called.

Any person could start a school if he could get a Magistrate to sign his application and state that he believed

applicant to be a fit person and that he had a proper school room. At the end of each month he or she the Teacher

sent to the Govt a filled up form giving the number of children who had attended, which had to be signed by a J.P.,

and the Teacher received from the Treasury One Shilling and eight pence per month for each child not being less

than 20 nor more than 40. This Ordinance which had only become law just before I arrived induced a great many

people to start little schools all around me and I had hard work to maintain my numbers, each one of these

mushroom schools taking away one or two children, tho' in the long run most of them would come back.

THE LOCKED JOURNAL

Page 4.

Before I go on to describe the incidents of the voyage, I must narrate a laughable story, in which I played a very

wicked part. Our Dr Maurau whom all my children will remember and esteem as “the Good” Doctor of Reynella

and my intimate friend for many years, was then a nice bashful young man, just married and only just passed as a

Surgeon, was as I have said, sent to assure us that the man had died of English Cholera. Among the many indignant

denials made, I who saw the point of a joke said, Dr I will prove to you, and you shall acknowledge that you are

wrong. Well said he if you put your opinion before that of the Health Officers I have no more to Say. Nay said I,

but you shall acknowledge that I am right. There was great silence, and I said quietly, Doctor, What is the name of

this ship. Amidst great laughter 50 voices replied “Asiatic” and the poor Dr made a hasty exit. It was too bad of me,

but I could not resist it, many a time since have we laughed together as he would recount this anecdote saying;

That I completely "sold" him. Alas! He is gone. Peace to his memory.

We sailed slowly down to the sea I remember passing Sheerness and the North Foreland and then came Chaos.

For two days and nights I lay in the utmost misery, how the poor children below us in their berths got on, I neither

knew nor could I help them I only thought I should die, when all at once we were still. We were inside the Plymouth

Breakwater, Oh what a respite, but only for a day. Next morning we were off again and the sea was calm, I

remember passing the Landsend and Eddystone Light, and felt very sad at taking farewell of the shores of my dear

old country, but what I thought of for several days after that it is impossible for me to describe, except that I deeply

regretted that I had ever put my foot on board ship, and felt sure we should all go to the bottom.

One day when it was a little calmer, Capt Waddell came down and made us all get up on deck. We were forced to

obey, and children and adults were all seated on either side of the cuddy and for a time we managed by holding on

tight to the bulwarks to enjoy in some measure the rays of the sun but it was of brief duration for the sky soon

clouded, the wind arose, a tremendous sea struck the vessel, and your Mother who sat on the opposite side from

me was sent spinning right across the ship down to me, and we all had to be assisted by the sailors down to our

bunks. A day or two more of misery, and then the Captain told us that we had crossed the Bay of Biscay and should

soon have calmer sailing.

This prediction proved correct, and getting more used to the ship and its ways we gradually found ourselves

more comfortable. But your mother could not relish the food allowed us nor did the children, and poor mother

often went hungry and longed for some more flour especially as she could not eat the ship's biscuits which they

ironically called bread, only a small quantity of flour being doled out to us which chiefly went for the children.

But we could not buy it, and so had to put up without it. As for myself, after I got over the sickness, I felt better

than I had been in England but still far from well and did not relish the food any more than the others.

On the next Sunday we had service on board. Passengers crew and all not engaged working the ship were

arranged around the cuddy, and the Rev Mr Cheetham a Congregational Minister who with his wife and family

were Steerage passengers with us, conducted the service which we greatly enjoyed. After dinner the first mate

announced that we were passing Teneriffe, and must look out for the Peak. We looked and looked in vain no sign

of land could we see, when all at once I looked above the white fleecy clouds which bounded the horizon and there

high above the clouds, in the pure blue ether, arose the Peak in all its magnificent grandeur. Its height, I think is

15,000 feet.

A few days after this we were becalmed and as we were getting into the tropics and nearing the equator the heat

became very great, while the fact of our being becalmed, and the offal of the ship lying all round about us caused

a stench to fill the ship almost unendurable. We were becalmed a fortnight and our [sic] became most distressing.

On the 5th October however things came to a climax in more than one respect. Your Mother was taken poorly in

the evening, and the Dr ordered her into the Hospital, which was hastily prepared for her and before midnight she

was safely delivered of our fourth daughter, Annie Oceana, now Mrs G W Padman. In the early morning while I

was sitting on the gangway steps talking with the Doctor’s Assistant, I exclaimed "The Ship's moving," Nonsense

said he, but I ran to the bulwarks, and sure enough she was going nicely thro' the water at two or three miles an

hour. Oh what a double relief. The birth of our child was entered in the ship's log as having occurred in lat. 6.35 N

and long. W 6 1/2 degrees North of the equator.

Crossing the Line.

Two days afterwards we were told that we should cross the line that evening, and a fat old cornishman on board

was very anxious to see the ship go over it, as he thought it was a veritable line or rope, so the first mate determined

to gratify him. We agreed that he should be awoke in the night, and scolded because he had not got up before we

had passed it, which the mate informed us we had done an hour before. The old man rudely awaked hurried on

deck his shirt tail floating in the wind, and exclaiming in true Cornish style. Where is her! I can't see her! 0h what

a pity! The mate said don't you [sic] that line pointing to a streak on the horizon. But the old man was not to be

gulled. "Her baint She” he said, "You be gammoning I." Well said the mate I'll convince you, and fetching his

telescope, he adroitly put a hair across the sight, and handed it to him. Amid roars of laughter the old man cried

out "There she be" "I see her" "Thankee Mr Metcalf" “I said home that I would see the line, and now I have seen

her" and went to his bunk quite satisfied.

When your Mother had been in the Hospital about 3 days the Captn. ordered the Medical comforts to be stopped

as she was doing well. I thought it very cruel, but there was no appeal, but when I saw her pining for want of proper

nourishment I was very indignant. Now all the money we possessed was 5 sovereigns which Mother had sewed

between the bones of her stays. So I said Mother, give me your stays but she refused, however I soon got them and

ripped out one, and got a bottle of Port Wine for her. Cost 5/-. She afterwards had another bottle and so she sewed

up the others and we arrived in Adelaide with £4-10-0 and 5 children. We had hoped to have had one sovereign for

each child.

We had by this time become used to the ship and sometimes greatly enjoyed ourselves when the weather was

calm and the sea moderate. For myself I felt so well and my appetite was so good that I could relish to the full the

coarse food provided. While your Mother was in the Hospital, I had of course the care of the children and had

enough to do, especially as our little Boy Joseph was very poorly and had a large boil or ulcer formed in his back

which required constant attention. The heat too being in the tropics was dreadful. It was then that I began to

experience a complete change in my physical nature. I began to perspire a thing I had never done before and so

freely that the bed would be almost wet through in the morning and had to be placed on the bulwarks to dry.

New found health.

My skin too, which had always been dry and hard like chicken flesh changed by degrees into a fair and clear skin

like that of a little child. It seemed as if I had done all the sweating of 33 years in almost as many hours.

Following this came a tremendous appetite, I would get up in the morning by 5 o'clock, and taking a Ship's Biscuit,

and knocking the weevil out of it, would put it on a tin plate covered with a good large slice of fat pork, put it in the

galley fire, and when cooked eat it with much gusto and Appetite. In fact I could eat anything, I had clearly turned

the corner and begun to live a new life, and thus the opinion of the Dr who examined me at Lynn was verified, that

I was not too far gone, if I had the benefit of a sea voyage and a change of climate.

This is 36 years since and I wish here to record my fervent thanks and praise to my gracious God and Father that

through that long period, I have had almost uninterrupted good health, and now in my 70th year the same great

blessing is still vouchsafed me. What shall I render unto the Lord for all his benefits. The Lord make me truly

thankful, Amen.

Nothing particular occurred during our voyage down the Atlantic. We rounded the Cape in fair weather crossed

the meridian of Greenwich and entered the Southern Ocean. I had put my watch right with Greenwich when

starting, and kept it always wound up of course we lost time at first going west and when off the South American

coast were several hours late, but I never altered my watch, and had the pleasure of finding, that it was almost right

with the ship's time when we crossed the first meridian. Then going East we began to gain time, till on arrival

at the Port I found my watch 9 1/2 hours late. But I am forestalling. We had made very slow progress going down

the Atlantic, but when we entered the Southern Ocean we had fine westerly and southerly winds and went on gaily.

Our old tub of a ship which foundered going home at Port Elizabeth in South Africa behaved nobly. Our baby

Oceana was getting on finely, a fat chubby infant, and our first mate Mr Metcalf, would often ask your Mother to

be allowed to nurse it. He said he had a family of his own in London. He would take the baby round among the

passengers and have a sly hit at some of the newly married women, among whom there had been two or three

failures on the voyage, saying "Ah! this is a really baby, none of your make believes." Your Mother too was much

better as were the children, and we were now all looking anxiously for the first sight of the New Country.

We passed within sight of St Paul where the Captain had promised to call for water, but when we sighted it resolved

not to lose any time, so we did not call.

It was on the 24th Decr we caught sight of Kangaroo Island, and the Captain promised us, that we should have

roast beef and plum pudding at Adelaide on Christmas day if we found it ourselves but we were doomed to

disappointment. On Christmas morning we entered the Gulf but were opposed by a very strong wind from the

North which we found afterwards was a hot wind. All that day we did nothing but tack from side to side making

but little or no progress. We saw "the goodly land and Lebanon" the Southern coast looked particularly inviting,

but could not enter it, and so, instead of dining on Christmas fare, we were doomed to regale ourselves on the

inevitable salt hunk. It was not till noon of the next day that we got to the Light Ship and there we found the

"Harry Lorregner" a fine new emigrant ship that had left London a month after us. Mr Timmins and Wife of

Nairne came out in her.

We did not arrive at the Port after all till evening but most of the male passengers went off to Adelaide at once.

I did not, I and Miss Griffin whom I have not mentioned before, went on shore, and walked as far as Alberton a

township about a mile or so from the Port, to see how we liked the new land. This young lady was an assistant in a

Drapers Shop in Lynn, and a Singer in the Congregational Chapel like myself. When she heard that I was going to

Adelaide she asked me only the Sunday before we sailed whether she could go out under our protection in the

single women's department. We agreed, and tho' she had only a few days to prepare, she was ready and went with

us on Thursday and sailed with us, not even going to see her aged parents, who lived in Hampshire, because there

was no time. I may here at once say that she got a situation as Governess in the family of the Hon W Duffield of

Gawler, and as that Gentleman got rich very fast their household became large, and she became Housekeeper and

General Manager of the household, entrusted her savings in the Mr Duffield's hands and in 15 years time saved

money enough to go home to England and to keep herself respectably but now I hear that she has been for years

past out here again, and is living at Mitcham.

Adelaide - a new life.

The next morning Miss Griffin and I started for Adelaide to seek our fortunes. The day was very hot and the sun

scorching. Our first visit was to Mr Geo Rolfe the only friend we knew in Adelaide who was one of the Deacons of

our Church in Lynn and who had emigrated about six months before we did, with his wife and two children.

He was a Draper in Lynn but had been insolvent, and all his available cash I was informed was about £100.

They had a most unfortunate voyage, lasting 6 1/2 months, and were nearly starved causing Mrs Rolfe to be

seriously ill and she died within a few weeks of landing. We found Mr Rolfe in business as a Land Agent, and doing

well. He was cousin to Mr Jno Morphett now Sir John a rich landowner, who doubtless put him into business.

He received us very kindly, but was very busy so we did not trouble him long. He asked me what I intended to do.

I said of course, school teaching was my profession. Oh! said he That is but poor work, Adelaide is full of little

schools and when a person can get nothing else to do they start teaching. What else can you do. Well said I,

I could fulfil the duties of a Clerk. Said he That is much worse the city is deluged with clerks of all sorts.

Can you do anything else? I said I could work at my trade of a tailor. Why said he, That is worst of all. This was

poor encouragement. But said he don't be dismayed, something will turn up in a few days.

Bring your wife and family to my House, we will manage to do somehow, and as tomorrow is Saturday, you can

sleep there on Saturday night and on Sunday I will introduce you to some friends who will be able to help you.

We then left him. In the afternoon we walked to Kensington to see old Mr Roberts, to whom I had a letter of

introduction from my brother Thomas who was on the Committee of my brother's School at Wem Shropshire

and reputed very rich. He received me very coolly, I thought, but when he opened the letter his manner changed.

Why said he, Have you got any testimonials as to your fitness as a teacher. If so, you are the very man we have been

looking for. We want to establish a Day School in connection with Freeman St Chapel but we will not do it until

we can find a regularly certificated British School Teacher. Well said I. Here he is shewing him my Certificate as

having passed through the Normal School and also testimonials from the three schools I had conducted in England.

He sent for the Rev Mr Strongman, the Congregational Minister of Kensington who examined my papers, and

entered heartily into the project, and Mr Roberts gave me a note to the Rev Mr Stow the Minister of Freeman St

Chapel which I was to deliver to him on the next day, at his residence at Paynham[sic].

Job search.

I then went back to the ship, very tired, but very hopeful. The next morning I was off again and saw Mr Rolfe who

was very glad to hear what had occurred and promised hearty assistance, and then started to walk to Payneham to

see Mr Stow. It was terribly hot, the distance 4 miles, and of course I lost my way, and wandered about for an hour

or more. I was told to make for the Maid and Magpie, but how to find either of them I did not know. I lay down by